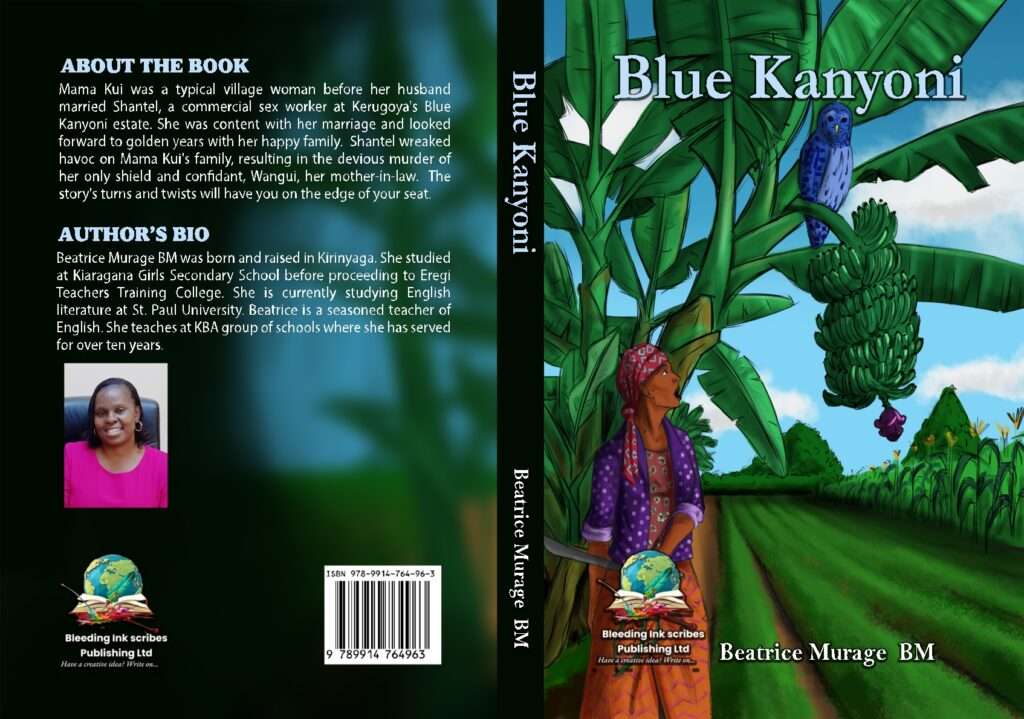

Title: Blue Kanyoni, Volume 1 by Beatrice Murage

PUBLISHER: Bleeding ink Scribes publishers limited (2024)

Reviewer: Bonface Otieno Okinyi.

Beatrice Murage’s Blue Kanyoni Volume 1 is a powerful rural domestic drama that explores the delicate interplay between tradition, gender roles, modernity, and betrayal within a central Kikuyu family. With poetic narration and biting social commentary, the novel introduces us to Mama Kui, a patient and dutiful wife, and Baba Kui, a man driven by patriarchal entitlement and naiveté, whose infidelity sets off a chain of emotional and material collapse.

The main conflict in Volume 1 stems from Baba Kui’s infatuation with Shantel, a seductress whose presence upends a stable family structure. The disintegration of domestic resources—livestock, property, and family harmony—mirrors Mama Kui’s growing anguish. Baba Kui’s choices reflect the failure of the African patriarch in adapting to moral responsibility amidst changing gender dynamics. The book addresses economic disenfranchisement, marital breakdown, and spiritual erosion as interwoven societal dilemmas.

Polygamy and betrayal, and betrayal takes the central stage as two of the major issues aesthetically addressed in this novel. Baba Kui’s fall from grace after pursuing a second wife unravels the security of his household. Shantel is symbolic of modern corruption and urban temptation. This is a major cause of dysfunctional families and how children from such homes suffers in the long run. The modern-day Kenya is a metaphor of this debut novel. Kui and Tim become bitter victims of this unwelcomed beast.

Gender roles and patriarchal tension is heavily touched. Mama Kui epitomizes the long-suffering woman, echoing Akoko in Grace Ogot’s The River and the Source, who silently upholds family despite injustice.

Loss and rural decay. The selling of trees, animals, and the forest signifies ecological and cultural disintegration. Closely, the issue of hope and resilience come out boldly in the face of traumatic experiences. Despite pain, Mama Kui remains emotionally anchored, embodying strength and self-restraint. She self-holds her family by the very pillars of its foundation.

Murage’s characters are deeply human. Mama Kui is vividly drawn with nuanced emotional reactions and maturity. Baba Kui is portrayed with tragic irony—both victim and villain of his own making. Shantel, though less psychologically deep, functions as a powerful disruptive force, almost an archetype of danger.

Murage’s prose is lush with imagery, similes, irony, and humour. The style balances pastoral lyricism with satirical realism. Scenes are cinematic—conveyed with clear visual, olfactory, and emotional sensations. Dialogue is organic, often laced with idiomatic Kikuyu-English hybridisation, enhancing authenticity.

Blue Kanyoni speaks to the contemporary Kenyan rural household grappling with modernization, fractured faith, and the cost of materialism. It critiques blind patriarchy, religious hypocrisy, and the erosion of moral values. In that regard, it functions as both mirror and cautionary tale—resonating with real communities experiencing similar upheavals.

Like The River and the Source, Blue Kanyoni elevates the female protagonist as the moral center. Both works explore generational transformation and gender dynamics, but whereas Ogot uses a historical lens, Murage offers a more domestic and satirical angle. The narrative also bears resemblance to David Mulwa’s Inheritance, where personal greed leads to communal destruction.

Vividly employing the Feminist theory, the author exposes patriarchal oppression and the endurance of women. Similarly, Postcolonial theory has been used adequately. Shantel and the bar represent neo-colonial corruption—urban modernity consuming the rural ideal.

Marxist theory. Economic instability is both a symptom and cause of moral decline. This text is very rich. Very significant and timely.