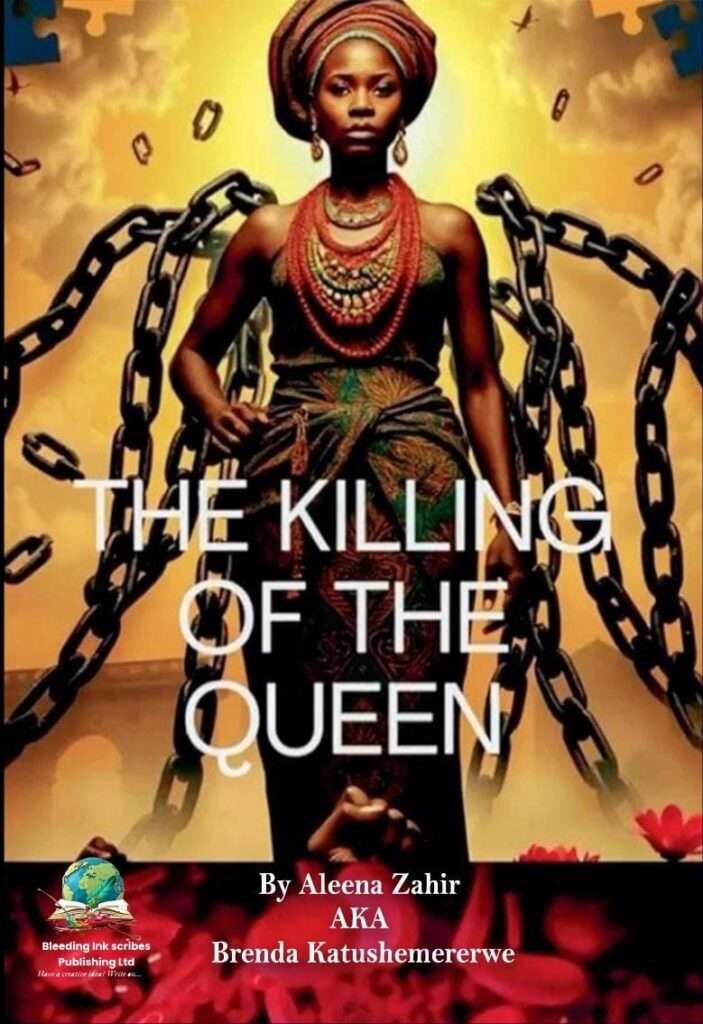

BOOK REVIEW: The Killing of the Queen

Author: Aleena Zahir (Brenda Katushemererwe)

Publisher: Bleeding Ink Publishers, Nairobi | Year: 2025

Reviewer: Alfred Nyagaka Nyamwange

Aleena Zahir is not just a name — she is a movement. At 32, the Ugandan artist, Pan-African activist, human rights advocate, and soulful musician has become a voice of her generation. Through songs like Wake Up, where she calls Africa to consciousness, Konyonza, a lyrical tribute to village life, We Rise, a bold prophecy of Africa’s renaissance, Humanity, her cry for justice and peace, and Woman, a raw reflection of the burdened yet unbroken African woman — Aleena sings truth into the world.

Her debut book, The Killing of the Queen, breathes the same feminist and Pan-African message, channeling the spiritual urgency and lyrical conviction found in her music. It is a fearless meditation on African womanhood — unflinching in its indictment of patriarchy, colonial legacy, religious control, and gender-based violence. Yet more than a lament, it is a vision: a call to restore the sacred dignity, leadership, and spiritual sovereignty of the African woman.

Aleena Zahir, the CEO of Bleeding Ink Scribes Publishers; Mr. Bonface Otieno Okinyi, CEO of Edulight International; Mr. Kelvin Nyamache, Mother Bantu; Elder Salongo; Jerusha Kananu, the award-winning author; and other Pan-Africans during the official launch of the debut, The Killing of the Queen, at Nairobi National Museum in Nairobi, Kenya.

Born of personal reflection and shaped by lived experiences — including a transformative encounter at a refugee camp and the birth of her son — Aleena’s voice fuses the personal and the political. She writes as a mother, artist, and activist, but also as a modern griot reviving forgotten truths, buried wisdoms, and sacred histories.

The book’s central metaphor — the “killed queen” — symbolizes the erasure of African women’s sacred, political, and cultural power. Aleena contends that this queen was not killed in a single act, but through colonization, religious distortion, sexual violence, and economic disempowerment. This symbolic death resulted in generational trauma and internalized inferiority — particularly among Black women.

Yet, the book’s core theme is restoration. Aleena calls for a radical reclamation of African womanhood — not by mimicking Western feminism, but by reviving precolonial traditions where women were warriors, spiritual leaders, healers, and custodians of justice. Through oral history and mythology, she resurrects the legacies of women like the queen mothers of Dahomey, the prophetesses of the Great Lakes, and the revolutionaries of Ethiopia and Zimbabwe — not as nostalgia, but as blueprints for transformation.

Intertwined with this is the theme of decolonization. Aleena critiques how colonialism not only took land but also rewrote gender roles. It weaponized patriarchy to entrench control and destabilize traditional African societies. Under colonial rule, communal practices rooted in mutuality were distorted, turning women into subordinates and silencing the divine feminine.

Aleena’s vision is fiercely intersectional. Poverty, for instance, is not treated as an economic condition alone but as a weapon — one that fuels labor trafficking, sex slavery, and the exploitation of domestic workers abroad. She links these systemic injustices to broken economies, foreign dependency, and corrupt leadership — all of which disproportionately impact women from marginalized communities.

Her critique also extends to spiritual exploitation. Aleena questions institutional religion, particularly its role in suppressing women’s agency. She condemns masculinized theology that prizes obedience over insight and silences women in sacred spaces. In contrast, she draws from African spiritual systems such as the Yoruba Orishas to restore balance, abundance, and the sacred feminine. Reclaiming queenhood, she argues, requires both spiritual and material revolution.

Her prose is poetic and emotive — shaped by personal stories and voices of women she has encountered. These include survivors of domestic abuse, victims of femicide, and mothers fighting for justice. Yet Aleena avoids reducing these women to victims. They emerge as warriors — broken but unbowed, resilient and regal. Her storytelling becomes both a lament and a testimony to survival.

She also critiques modern masculinity. Aleena calls out the erosion of responsible male leadership — what she terms “abdicated kingship.” In a culture where dominance, emotional detachment, and material conquest are glorified, she challenges men to reclaim their roles not as rulers but as nurturers and protectors. She calls for a redefinition of manhood rooted in humility, empathy, and partnership.

Importantly, Aleena does not advocate replacing patriarchy with matriarchy. Her vision is one of balance — a restoration of harmony where men and women lead together. She proposes practical reforms: fair division of domestic labor, community-based mental health support for mothers, and educational systems that affirm both girls and boys.

Voice and visibility emerge as central to this liberation. Aleena urges that women’s ideas, stories, and leadership must be centered in Africa’s cultural and political rebirth. She is particularly scathing of social trends that demean women — including ageism, slut-shaming, and the glorification of toxic masculinity on social media. These, she insists, are not trivial matters but cultural viruses that distort identity and intimacy.

She also critiques Africa’s education systems, which she describes as “colonial classrooms” — institutions that produce mimicry instead of innovation. According to Aleena, true education must be rooted in indigenous knowledge, local languages, ethical values, and agricultural self-sufficiency. Liberation, she argues, must begin in the mind.

Stylistically, Aleena’s book is defiantly non-academic. She writes from memory, song, and oral tradition, dispensing with footnotes in favor of emotional and cultural truth. While this strengthens its accessibility and authenticity, it occasionally weakens its analytical rigor. Nonetheless, her message is clear: African knowledge does not need Western validation to be legitimate.

Ultimately, The Killing of the Queen is not merely a book — it is a cultural intervention. It dismantles myths, confronts power, and declares truth as a healing force. Aleena calls African women to rise — not by imitating others, but by becoming whole again. She calls African men to return — not to the throne of dominance, but to the altar of service.

Aleena Zahir sheds light on her debut book during the official launch of the book in Nairobi, Kenya. The launch was organised by Bleeding Ink Publishers and the Pan-African organisation AFFAD, led by Aleena Zahir, in April 2025.

Her work is holistic. She weaves together the lyrical and the political, the personal and the ancestral. She offers no easy answers but demands necessary questions. Her tone moves between rage and tenderness, urgency and wisdom — but always with clarity: Africa cannot rise if its queens remain buried.

At its essence, The Killing of the Queen is a cry against silence, shame, and forgetting. It invites readers — especially women — to emerge from erasure and reclaim their ancestral crowns. It is both a eulogy and a vision — mourning what has been lost while prophesying what can still be found.

Still, the book is not without flaws. The lack of structural clarity between the introduction and first chapter occasionally blurs the thematic trajectory. Aleena’s impassioned commentary, while powerful, sometimes disrupts flow and coherence. She should have borrowed from John Maxwell and Paul Coelho’s simple thematic and personal approaches so that three volumes would have come from this single manuscript. The narrative could benefit from tighter editing — removing occasional clichés, clarifying chapter titles, and avoiding inconsistent pronoun use. Her decision to avoid citations, though intentional, leaves some factual claims vulnerable. Moreover, the wide thematic scope — spanning politics, family, economy, and spirituality — sometimes dilutes focus. Despite this, her unyielding voice, vision, and passion ensure the book’s impact.

In sum, The Killing of the Queen stands as a potent debut. It draws inspiration from the legacies of powerful African empires and figures — from the Kandakes of Kush and Queen Njinga of Ndongo to the queen mothers of Benin and Ethiopia. Aleena’s work honors their memory and reimagines their spirit for the modern age. Though imperfect, her book is a bold offering — part history, part healing, part hope. It marks the rise of a new griot — one who sings, writes, and fights in the name of the queen.

The literary gangster/guru, award-winning poet, and recipient of many other distinguished awards, Tony Mochama, and his son Leo. Tony gives a deconstructing talk about literature and pan-africanism in the contemporary society during the book launch